Forward

In preparation for the upcoming COP27, the UN World Urban Forum and the ISOCARP World Planning Congress, ISOCARP members took the initiative to put together this Special Newsletter to share Climate related updates and opinions with the community. We would like to warmly thank Pietro Elisei, Martina Juvara, Elisabeth Belpair, Ali Alraouf, Khalid El Adli, Abbas El Zafarany and Huda Shaka for their contribution.

Introduction

Cities play a critical role in our multiple crises: they are leading sources of GHG emissions, but also the places where different aspects of the climate crisis overlap and where strong responses are needed for a fair and just transition. It’s clear that the way cities are planned and managed needs to drastically change if we are serious about meeting ambitious but necessary targets for emission reduction and adaptation to a changing climate.

Action is now finally being taken by many city leaders, but is this approach enough to deliver the radical transformation our cities need to make good on our promises?

Martina Juvara, strategic and master planner, Director of URBAN Silence and ISOCARP Member. Martina led the ISOCARP delegation to COP26 in Glasgow.

ISOCARP and Climate Action – by Pietro Elisei

The ISOCARP World Planning Congress, due to take place in the first week of October in Brussels, has a very significant title: from Wealthy to Healthy cities. Its emphasis is on a “just transition for a better world”!

Within a just transition there are all the elements necessary to build a sustainable future, but there is also a very strong collateral message: the risks associated with development models oriented purely to the search for profit are putting quality of life at risk, both in urban contexts and in the very delicate balance of natural ecosystems, on which the survival of our species depends.

Sustainable economic growth, the reduction of economic disparities between cities, regions and nations are important, relevant challenges, but we cannot possibly attain them without considering the environmental factor. In this sense, investments in the transition to an ecologically balanced future are more fundamental than ever in any urban strategy that has vision, coherence and concreteness.

An ecological transition that must be built together with local communities, which must be locally rooted, and which takes into account the diversity of local contexts, but which starts from those principles of good planning, of global value, which must be understood everywhere, namely:

- Contemporary urban transformations must consider both mitigation and adaptation actions to climate change.

- In every city, regardless of its scale, everything must be done to pursue models of sustainable mobility.

- The energy problem in the urban context must not be tackled with sectoral solutions, but through an integrated approach that holds together renewable and non-renewable sources, in the medium term, but tends to pursue a zero net impact in the long term.

- To fully understand in urban contexts the value of planning through Nature Based Solutions and calculate the added value, also in economic terms, of the ecosystem services generated by this type of architectural and landscape solutions and their support to the strengthening of natural ecosystems.

- Creating resilience in cities through a full implementation of an integrated urban approach, which means: pluralism, inclusive planning, less top-down imposed technicalities and greater dialogue between public and private actors. A resilience that passes more through the design of innovative urban policies, which takes into account local complexities, both in terms of different interests in continuous comparison, but also in terms of an alternative to deterministic and obsolete planning systems.

ISOCARP, made of its two components – the Society linked to the organization of events and publications, and the ISOCARP Institute, representing excellence in applied research – is at the forefront of promoting innovation, good planning, dissemination of good practice linked to issues related to managing the ecological transition in the best possible way and obtaining concrete results to reduce the risks associated with the contemporary and evident risks triggered by the ongoing climate change.

– by Pietro Elisei, town and regional planner, senior researcher, ISOCARP President and Executive Committee Member

Update on COP and the IPCC – by Martina Juvara

COP26 (November 2021) was a watershed moment in understanding the importance of spatial planning in Climate Action. The theme of human settlements and the built environment had a dedicated day (albeit the last of COP, when everyone was focused on the negotiations) and lots was going on – see the summary made the Built Environment Climate Champions of the UNFCCC: Top of the COP: Cities, Regions & the Built Environment – Climate Champions (unfccc.int).

What also became apparent was that the NDC (the Nationally Determined Contributions, i.e. the voluntary pledges towards carbon reduction made by individual states every 5 years) were coming woefully short of the carbon reduction curve agreed in the Paris Agreement (at COP21). In richer countries, such as the G20 which are responsible for 75% of global emissions, cities are by far the largest emitters – and yet their role in the fight to control greenhouse gases (GHG) was not yet coming into play. Very clearly, simply addressing energy production, industry and transport was not enough. For this reason, all nations agreed to renew and republish their pledges or NDCs on an annual basis, starting with 2022 and in time for COP27 in Egypt next November.

Somehow, because it was not a particular subject of discussions in the halls and corridors of COP, the importance of cities and planning made it into the official text of the Glasgow Climate Pact (COP26 cover decision (unfccc.int) at point 8, where it is stated that The Conference of the Parties (COP) urges Parties to further integrate adaptation into local, national and regional planning. This is a clear recognition, at national and political level, that planning has a key role to play in climate action.

This message has been further reinforced by the partial release in April 2022 of AR6, the Assessment Report of the Independent Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) – Sixth Assessment Report — IPCC. The Report dedicates the 100-page+ Chapter 8 to cities and makes some strong assertions for the attention of policy-makers: the urban share of GHG emissions is substantive and continues to rise, but the growing concentration of people and activities in urban areas is also an opportunity to increase resource efficiency and at scale. In plain language, this means what planners have been arguing for years: without

addressing the urban form and operation of cities, we simply cannot achieve the targets required to keep the climate emergency under control.

Chapter 8 makes also other interesting assertions:

- It makes a link with SDG11 and supports the recommendations of the New Urban Agenda, particularly for its call for integrated spatial planning at the city-regional scale.

- The focus on urban areas as a ‘system’: the interdependency of settlements with other cities and regions, their reliance on systems of governance, economy, ecology and infrastructure that are broader than the city itself but also the ecosystems of interconnectedness within the city itself. Particularly, changes in urban form and infrastructure can simultaneously affect multiple sectors, such as buildings, energy and transport (paragraph 8.1.3). This is the strongest admission yet that simply focusing on zero emission buildings or electric cars will not be enough.

- It recognises that cities are not only big emitters (mainly by burning fossil fuels and by consuming materials and goods produced elsewhere) but also accumulate carbon in urban pools, such as vegetation, soils, building stock and even landfills. Any strategy requires therefore both reducing emissions and enhancing carbon uptake in the existing pools.

- There are no univocal and widely used methodologies for carbon accounting in cities, probably a main reason why no urban pledges are made in the countries NDCs. However, four main and complementary frameworks are emerging to account for territorial carbon, infrastructure, consumption and personal carbon footprints of citizens. Maybe we are not far from a breakthrough.

- In cities, the co-benefits of urban mitigation strategies can be wide ranging, including public saving, health, equality etc. Urban areas have the unique potential to tackle GHG reduction, better adaptation to climate shock, population resilience together with wider and broader sustainable development goals (health, wealth, inclusion, resilience, participation, etc).

- Urban emissions are driven by economic growth and increased consumption associated with the higher income of city dwellers. There is some evidence that the energy efficiency of denser and compact urban systems is often offset by higher consumption patterns.

- While urban population is expected to grow, the form of expansion it will take can vary significantly according to different scenarios and integrated planning of land use, urban form, transportation, energy systems and especially specific strategies for decarbonisation and development of efficient carbon sinks.

- Compact and walkable urban form is strongly correlated with low GHG emissions and characterized by co-located medium to high densities of housing and jobs, high street density, small block size, and mixed land use. Higher population densities at places of origin (e. g., home) and destination (e. g. employment, shopping) concentrate demand and are necessary for sustainable mobility.

- Urban green and blue infrastructure and Nature Based Solutions involve the protection, sustainable management, and restoration of natural or modified ecosystems while simultaneously providing co-benefits for human well-being and biodiversity.

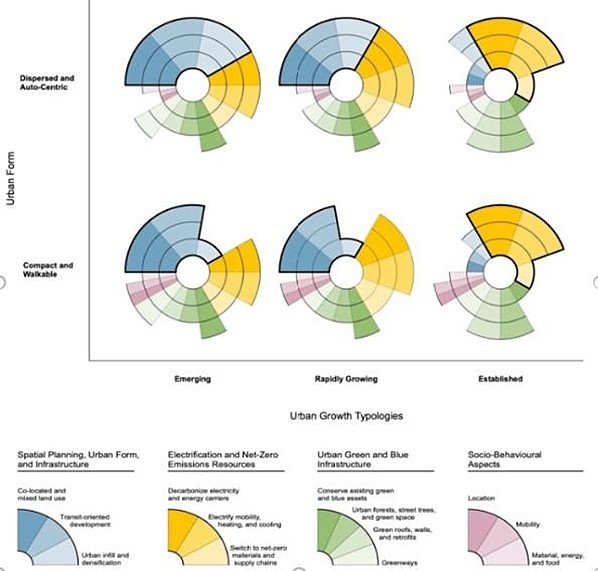

- Very importantly, the impact of different strategies is different depending on the urban system in which they are applied. While all cities depend on net-zero energy resources, green and blue infrastructure plays a significant role and spatial planning and urban form is critical to all expanding cities.

Priorities and potentials for packages of urban mitigation strategies across typologies of 2 urban growth and urban form.

Source: IPCC AR6 Report Chapter 8, Fig. 8.21

– by Martina Juvara, strategic planner and master planner, Director of URBAN Silence and ISOCARP Member

Women in Planning for Climate Action – by Elisabeth Belpaire

A snapshot of the participants in the discussion (Source: Elisabeth Belpaire, CA#7).

Cyber Agora #7 on Climate Action and Women in Planning was an extraordinary event, with relevant and memorable outcomes. CA#7 put a spotlight on women planners insights and how they lead on urban and spatial planning for climate action. It also challenged the status quo on the state of affairs on the participation especially in planning and tackling climate change. Perspectives were diverse and rich, as you would expect from four different corners of the world and different generations. Yet common observations are that what planners and cities do today matters. Things are not getting better fast enough. We are seeing more women in planning – and they are having an impact – and there is more recognition of gender issues in the planned space, yet the change is slow. Climate change on the other hand is fast. There is both urgency and opportunity. Here a few key insights:

- On the untapped opportunity of underground urbanism: Underground space has an important role and offers a wealth of possibilities for climate mitigation, adaptation and emergency response. For example the subsoil functioning as storage and run off facility of water; underground transport systems that can move millions of people and act as emergency relief systems and shelter during natural (but also manmade) disasters. The subsurface to power and cool our cities and inform the base layer for green spaces and energy transition. All this we need to manage carefully and wisely and integrate it with our urban planning efforts on the surface. That way our cities can become more resilient and sustainable.

- On the promising step of connecting: The Climate Action Plan for Mumbai, India’s first, is an apparent meticulous and broad ranging strategy, which goes beyond technical solutions and physical interventions to address also issues of organisation and co-ordination. The human aspect of grand schemes like this is about connecting things. Women’s thinking in action: collaboration and communication are critical, across sectors, departments, genders, creating ripple effects throughout whole communities, inspiring other cities in the country, and beyond.

- On embedding the ethics of care: The climate crisis is a moral crisis and the response must be based on an ‘ethics of care’. The environment is a public good and the planners must care for it in the public interest and through gender equality. Women and girls are on the frontlines of climate crisis and are first responders in Sub Saharan Africa (SSA). The ‘feminisation of poverty’ and patriarchal hegemony are some of the challenges. The complexity of this old problem, now interwoven with the changing climate, demands an approach based on ‘connectional intelligence’, a capacity which goes beyond the traditional, technical planning expertise.

- On women’s participation and leadership: In Japan there’s poor representation of women in both the planning (and climate and engineering) profession and planning academia. Deep cultural traditions as the main reason for this and the speaker argued that unless we get more women in planning schools (both students and teaching positions), we will fail to get more women in the profession. The roots of women’s under-representation in planning are deep and subtle, and often outside the reach of conventional incentives. On SSA, the speaker lifts the role of the ‘Planneress’: women planners should be gender champions in tackling climate through spatial and land use planning, and with a special focus on vulnerable land and spaces. Women should take the lead in precarious communities and educate women and girls on reduction of carbon footprints. Planning and leadership should be based on ‘lived realities’ and for climate, liveability and health.

You can (re)watch the Cyber Agora and find more insights from speakers Antonia Cornaro, Lubaina Rangwala, Olusola Olufemi, Urara Takaseki, commentators Hope Magidimisha and Dushko Bogunovich, and curators Elisabeth Belpaire and Juanee Cilliers here: https://isocarp.org/activities/isocarpolis/cyber-agora/cyber-agora-7-women-in-planning/

– by Elisabeth Belpaire, engineer architect, urban and spatial planner and ISOCAPR Executive Committee Member

Gulf Cities in transition: from grey to green / From oil to soil – by Prof. Ali Alraouf

The sprawling of Gulf cities in the last few decades is unprecedented and transform all of them into car-based cities, the case of Doha in the last eight decades (Source: Prof. Ali Alraouf).

Spatial planning is becoming more and more relevant to action on climate change. Transformation of existing contemporary Gulf cities and a new approach to the future are both needed. In few months, experts will gather from all over the globe one more time for COP 27 (in Egypt this time) to discuss how to cooperate to address the impact of climate change. Urban planners are preparing to be more vocal, with a critical position stating that a thorough change in urban development strategies and lifestyles is needed. My focus, presented during UN MENA Climate Week 2022, is on Gulf Cities in the Middle East. Due to the oil revenues, all Gulf cities had an unprecedented pace of urbanity, which stretched cities in a horizontal manner, allowing cars to dominate the structure and patterns of mobility within the cities.

Globally or regionally, three existential challenges can by articulated:

- Oil: Gulf cities are swiftly approaching the post-oil paradigm. Oil, which is the backbone of their economy, is facing two main realities. First is depletion as in the case of cities like Manama, Bahrain; Dubai, UAE; Muscat, Oman. Second is the green deal and the global move towards renewable energy sources and commitment to reduce reliance on fossil fuels at global scale.

- Covid: The pandemic showed us clearly that all the glitzy towers and skyscrapers, huge shopping malls and even sacred mosques were closed and deserted. People were longing for green spaces and walkable neighbourhoods to overcome the consequences of an extended lockdown. Some of these new habits may become permanent.

- Climate Change: All the main Gulf cities are port cities which used to rely on fishing and pearl diving before the discovery of oil. Such a geographic legacy and locations along the water edge make most Gulf cities critically vulnerable to the impact of climate change and sea level rise.

How can urban planners provide a tangible change? This is an existential question requiring a solid of understanding of existing challenges in contemporary Gulf cities and of implementable transformations which can be adopted by city planners and authorities. Planning strategies and policies to better guide contemporary Gulf cities should be centred on finding balance between achieving the aspirations of its communities for excellent quality of life and minimise the negative impact on the environment and the contribution in the global warming. Considering the peculiarities of contemporary Gulf cities, three main approaches are suggested:

- From car-based urbanity to adopting TOD (Doha Metro) approaches

- From scattered urbanity to compacted districts and neighbourhoods

- From mall- based entertainment to green and open spaces for all with a holistic and comprehensive approach towards Healthy Cities.

Such approaches would construct a new paradigm in the urbanity of Gulf cities, marked by a long-anticipated transformation from spectacular urbanity to people-based places and spaces in future Gulf cities.

Doha, Qatar as an example of Gulf cities moving beyond spectacle urbanity and planning green spaces and vibrant public places for people to enjoy (Source: Prof. Ali Alraouf).

The shift from gray to green would create vibrant public places for people, promotes healthy lifestyle and attain food security from urban agriculture (Source: Prof. Ali Alraouf).

– Ali Alraouf, PhD, Prof of Architecture and Urbanism and ISOCARP Board Member

Cities and the Danger of Doing Not Enough – by Khalid El Adli & Abbas El Zafarany

The growth of cities comes at the expense of precious natural resources; it increases carbon emissions, pollutes the atmosphere, and results in local urban heat islands which in turn leads to global climate change. Yet, city growth is a consequence of consumerism rather than a tangible human need in itself. Global warming and climate change constitute major challenges with consequences for cities, coastal areas, agriculture, water management, hydro-electric energy, as well as summer and winter tourism. Floods, droughts, heat waves, wildfires, and increased tropical storms are sources of significant impacts and are of critical relevance for spatial planning. Mitigation and adaptation strategies including environmental protection, risk management, and hazard mitigation are thus necessary if cities are to withstand and safely accommodate threats associated with climate change.

The growth of cities comes at the expense of precious natural resources; yet, city growth is a consequence of consumerism rather than a tangible human need in itself. On the one hand, larger houses in low density suburbs with limited public transit increase carbon emissions. On the other hand, building new homes and abandoning the old exhausts valuable resources, consumes additional energy, and devastates existing communities. Still, these trends are still accelerating in many world cities, where real estate development positions cities as prime carbon emitters all while promoting a non-sustainable lifestyle. A paradigm shift that emphasizes sustainable liveability rather than consumerism (and growth at all costs) is hence indispensable.

The great city of Cairo is no different from other world cities, more and more suburban gated communities are being developed and promoted at the fringes of the city. A significant proportion of middle-class Cairenes are abandoning their old homes to newly built residential communities in suburbia. This depopulation has degraded urban quality in city centres, rapidly increased urban heat islands alongside urban growth, and created hot spots that are 6º C warmer than average urbanized areas. If this trend persists, with less green areas to mitigate the UHI effect, a further surge in temperatures could be anticipated in the future causing an increase in consumption of cooling energy coupled with reduced opportunities for outdoor activities.

Urban consolidation of city centres is thus crucial. Consumerism driven urban sprawl should be discouraged, green areas increased, public transport endorsed, energy efficient building practices enforced, and outdoor active lifestyle encouraged. Without such measures both our cities and the world will pay a colossal price for their emissions.

– Khalid El Adli, Principal Partner & Managing Director at EAG Consulting; Professor of Urban Planning and Design & Director of International Programs at Cairo University; Chair of Heliopolis Housing & Development; Former Governor of Giza and ISOCARP Member

-Abbas El Zafarany, Professor of Environmental Design, Former Dean of the Faculty of Urban & Regional Planning at Cairo University (2015-2019) and ISOCARP Member

The importance of climate adaptation at city-level -by Huda Shaka

On the race towards net zero emissions, it is important for cities to not lose sight of the other side of the climate change challenge: adaptation. While mitigation focuses on controlling the cause of climate change (i.e., reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions which lead to global warming), adaptation is about managing and reducing the wide range of risks associated with climate change. Unfortunately, the inequality of the world we live in today means that some of the lowest emitters of GHG are also some of the most vulnerable to climate change impacts. In those regions of the world, adaptation takes on an even more critical role.

Given its strategic, long-term outlook, urban planning is key to adaption efforts. Whether it is adapting coastal developments for the risks of sea level rise, planning and designing public spaces to be functional even during extreme weather events, or providing resilience through multi-modal transport networks – urban planners are an important part of planning for and implementing climate adaptation. Although adaptation planning can happen at many scales from the national to the local, it is often the local city level which is the most effective in making urgent decisions informed by the local needs and context.

To begin the journey of climate change adaptation, city officials must map out the specific climate change impacts for their city including impacts on human health and physical and natural assets. Involving the community, specifically the underprivileged and the most vulnerable, is an important part of this exercise. Once the impacts are evaluated according to magnitude and likelihood, appropriate adaptation measures can be identified to reduce risks to acceptable levels. These measures must then be incorporated into new and ongoing plans and projects, and their implementation will have to be monitored to assess whether any further action is needed.

– by Huda Shaka, planner, environmental specialist and Advisor for the Department of Municipalities and Transport in Abu Dhabi, ISOCARP Member

Key Events and Dates

World Urban Forum

Katowice, Poland

June 26-30, 2022

58th ISOCARP World Planning Congress

Brussels, Belgium

October 3-6, 2022

UN Conference of the Parties COP 27

Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt

November 6-18, 2022