The report of Martina Juvara, who led the ISOCARP delegation to COP26 in Glasgow.

Is COP26 just Blah Blah Blah?

Greta Thunberg was out in Glasgow, accusing COP26 to be just Blah Blah Blah: a smokescreen for protecting the status quo and the wealth of multinational companies. Other social media influencers have latched on the same message and are making it the ‘truth’.

Why, then, did all these people bothered?

COPs might have been narrowly focused events for negotiators in the past, but they are now set on a course of multiple goals and potential routes to success. The first route comes from global public pressure, protesters and marches, which none of us inside the ‘tent’ of the Blue Zone could hear or see in real life, but which was nonetheless acutely present: a force that pushed politicians, administrators and companies to show up and commit to greater ambition in front of the camera and other nations. Public opinion has potential to be a powerful enabler and the days of COP26 provided a clear and effective catalyst for people to be gather and try to be heard. The protests outside gave, for example, the younger official representatives of YOUNGO (Young People Non Government Organisation) essential presence in all major official events. Powerful opinions for radical change echoed in most discussions.

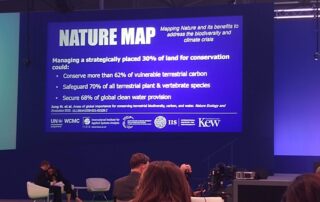

In addition, the programmes of multi-lateral cooperation and pilot initiatives born through dialogue at the COPs are vast: from finance to capacity building, technology, equality, ecosystems, etc. They involve nations and institutions cooperating with others to achieve a result, share knowledge and allocate funding for climate actions. This work leads to real change even if it never reaches the stage of an international agreement. Supermarkets are committing to a supply chain that does not lead to deforestation; youth groups develop a cross-boundary independent agenda for the future; financial instruments are increasingly tied to climate responsibilities, etc. Cities and regions are very active in this space, forming networks of mutual support, knowledge sharing and petitions for funding.

The third strand is that of the official negotiations: definitely hard and relatively opaque. The outcomes are doubted by many to have limited bite.

The reasons are difficult to overcome (see post on UNFCCC limitations) and are best accepted as they are. Nations have different priorities: for some reducing emissions needs to come with protection of lifestyles; for others it is preparedness to climate emergency and for small island nations it is outright survival. With these big differences and the requirement to progress by consensus, it is not a surprise that legal agreements and official declarations are not easy – but coming together every year makes it much easier for all to move in the same direction. Since COP21, in just 5 years, all nations firmly agree to “keep 1.5 C” and the principle of a just transition. Most countries also agree to make themselves available to international scrutiny. Not all promises will be kept, but without COPs there will be no promises at all. There will only be partial and self-interested perspectives. So no, COP26 is far from being blah blah blah – it is a complex and positive force. But will it be fast enough?

The Power of Influencers

I have been told that never before celebrities and influencers were present at COP26: from politicians with clout to actors to very energetic activists. Among them, there was an openly moved Gael Garcia Bernal, actor and broadcaster, talking about the emotional difficulties of leaving the world we knew behind, and realising that our relationship with the planet will be a different one. Like Gen Z are the first digital natives, soon there will be a generation of climate action natives – young people that will not have known anything else than the need to act to stabilise our climate. Frans Timmermans, the chief negotiator of the European Union, echoed the same sentiment in the official sessions: showing a picture of his grandson with a future of peaceful but vigilant climate awareness, if the world succeeds, or a future fighting for shelter, food and water – even in Europe.

Al Gore gave an amazing 90 minutes show with graphs and clips of climate disaster after disaster and undeniable data evidence. Captivating, but clearly nothing the people there did not already know. Barack Obama, Alexandria Ocasio Cortez, Nancy Pelosi, Idris Elba and more were there. Nevertheless, for many of us, especially in advanced economy countries, we naturally resist this thought and want to believe that nothing much will change. Most experts say we are wrong.

But the big bang of the conference came from various talks from young people. Climate anxiety? Absolutely a rational response! Without it, without feeling uncomfortable about the future, we cannot possibly have the mass mobilisation and mindset switch necessary to embrace a new way of life. The problem, however, is that young people are not yet given the space to reimagine the future. They are invited to events, consulted but within the framework of a way of doing things that will not change. Best thing for us professional to do? Remove our blinkers: mitigation without radical economic change will not happen, resilience without fairness is impossible, access to climate emergency training from a young age and throughout life are a necessity.

The UNFCCC operation and limitation

There may be frustration in some people: how come progress has been so slow? Is this even legitimate?

The United Nations Framework Convention for Climate Change (an unpronounceable UNFCCC) is steeped in international legalities, bureaucratic protocols and incomprehensible language. It is as user friendly as a spaceship repair manual. But, for what it is, it has achieved great things.

The United Nations can only interfere in international affairs and where there is danger for the population. When UNFCCC started to operate in 1994 scientific evidence of climate change was not univocal and the likely danger not so well understood. Its legal basis was the 1987 Montreal

Protocol that bound UN member states to act in the interest of human safety even in face of scientific uncertainty.

The remit of the Convention was agreed to be the stabilisation of dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system while protecting food production and enabling economic development. The Kyoto Protocol of 1997, but entered into force in 2005, established the principle that industrialised countries and countries in transition had to reduce emissions and report periodically to the Parties (i.e. the signatory nations). Only with the Paris Agreement of 2015, the target of 1.5 C / well-below 2 C emerged.

The weakness of the Convention comes from three sides:

- It is only recently that climate change has been ‘proven’ to be dangerous and to be, without reservations, caused by human activity. While this was in question, the legal remit of the UNFCCC was also in doubt.

- While the overall reduction of emissions and stabilisation of danger is legitimately a global remit, how the reduction is actually implemented is largely a matter of domestic policy outside the scope of the UN. For this reason, nations are free to develop ‘Nationally Determined Contributions’ (NDCs) on a voluntary basis and part of a global effort. Funding contributions to poorer nations follow the same principle of dialogue and voluntary pledges. This is a great challenge and a reason for the slow progress so far.

- Because of the mixed global and domestic scope of dealing with climate change, any protocol, agreement or pact needs to be unanimously accepted and then ratified by each nation. Because consensus is essential, compromise is inevitable.

The Glasgow Climate Pact is another step in the right direction: very importantly, it resolves to limit temperature increases to 1.5 C above pre-industrial levels, rather than ‘well below 2 C’, now recognised by scientists as too dangerous. It also requires annual reporting, with the next round of NDCs due by end of 2022 rather than 2025. This makes planning and implementing reductions a pressing political matter, which will no longer be deferred to the next political cycle.

The Pact also recognises explicitly the rights of indigenous peoples, migrants, children, young people and women as well as the right to development; it also recognises the value of adaptation and the duty of real operational assistance for loss and damage. These are great steps forward, although “not as progressive as it should be” according to my fellow guest at the hotel, one of the negotiators from Chile.

Top-Down vs. Bottom-Up

The great dichotomy of top-down or bottom-up approaches has been very evident at COP26, at very many levels.

The biggest difference of all is in the attitude towards adaptation between the advanced and polluting economies, which target national investment in innovation as the main solution, and lower income countries, who do not have big reserves for national investment and have a much more diffused economy: they prefer to adopt a mix of capacity building, traditional adaptation measures and restoration of natural environments. This is what we now call “nature-based solutions”.

This difference is not just driven by resources: in western democracies by delegation, people expect that the government “will sort it out”. In poorer countries, delegating upwards is unlikely to be fast and effective, and so communities get self-organised, counting on some public support and hopefully appropriate international funding but surely not expecting ready-made solutions.

Whenever governments lead the initiatives, projects are commissioned to professionals and scrupulously assessed in terms of performance and benefits against cost. Rulebooks and assessments methodologies are developed and published and they become the key routes to funding and implementation. This leads to technocratic solutions that give the appearance of certainty, such as the result of a flooding model by which a concrete flood defence wall is easier to model and predict than a sand dune beach restoration. This approach ends up privileging very expensive hard engineered solution to nature-based ones. Moreover, this process – the appointment of professionals, technical assessments, viability and benefit calculations – is incomprehensible for normal citizens, who feel excluded from the decision making and disengaged from climate action.

This preference for hard engineering is seen, by many poorer countries, as a great obstacle to justice because it could be an excuse to withhold funding or a way to promote expensive consultancies and engineering ‘take-overs’ by richer nations rather than investing in local competence.

We, as professionals, have to be inspired by the work that lower income countries have been doing: creating full systems of innovation-enabled nature based solutions that start from communities, small businesses, women and youths. This places people at the heart of the solutions, it has been proven to be very effective value for money and can speed up change. “Adaptation to climate events must be a way of life,” said the Minister of Environment of Japan.

Innovation

Investment in innovation is clearly the priority and focus of some key nations: the US, UK and Denmark had fiercely competing programmes of talks about green finance, energy, transport and logistics innovation. It is very evident that while innovation is advancing very rapidly, it will have only a marginal role in the ‘transition decade’ to 2030, by which time the Glasgow Climate Pact commits us to reducing global carbon dioxide emissions by 45% relative to the 2010 level. John Kerry, head of the US delegation, very openly stated that, as of today, counting on innovation is a distraction.

This does not mean that companies are not working hard at the Race to Zero: from green concrete and steel for construction, carbon capture, hydrogen shipping to zero emission vehicles. But every aspect of innovation requires initial backing for research and development, incentives and restrictions. The role of governments and of multi-party agreement is essential, and regulation alone will not be fast enough for innovation to be effective: Green Shipping Corridors, able to host hydrogen-fuelled ships, are possible – but require international standards and infrastructure. The State of California developed already a decade ago a programme of vehicle design, financial incentives and progressive regulatory restrictions that eventually made electrification of service vehicles (waste truck for example) and logistics the most advanced and efficient in the world. IKEA, which aims to reach 100% emission free home delivery services in various European countries and South America by 2025, has started to invest directly in its delivery providers to support vehicle acquisition, service planning and skill development.

The International Transport Workers Federation argued that new models of transport and innovation should also lead to better jobs: not only drivers and seafarers but also new technicians, data analysts, service planners and fleet managers. The next 10-year transition period will be hard: all innovation will compete for creativity and funding, and also chase the same sources of renewable energy – while at the same time polluting industries and fossil fuels will become more expensive, as they will receive fewer investment and less favourable credit. Scrappage or recycle of old technologies, including 1.4 billion fossil fuel cars, will be major undertakings.

Cities and Regions

Cities and Regions Day confirmed that cities intended as the human ecosystem of people, movement, activities, buildings, nature and infrastructure are not a prominent issue for UNFCCC / the COP official programme. The theme appeared only twice in the past 26 COPs: in Paris and now Glasgow. There have been only a handful of pledges concerning the built environment, and mostly have to do with the use of materials in buildings. Systematic change for cities and a new economic and social framework for a just transition has been loudly advocated by various youth leaders and activist groups, but it has yet to be received as a proper theme at the national and international scale.

A Human Settlements Pathway, however, has been set up by UNFCCC and has a Climate Champion tasked with moving the agenda along. As a result, several groups and coalitions have been set up either of cities or regions or a mix of both. For example, the forthcoming Mission Innovation no. 4, part of a global initiative of 22 countries and the European Commission catalysing action and investment in research and demonstration projects to progress towards the 1.5 C goal and pathways to net zero, will be dedicated to cities, but I have been told will mainly concentrate of building efficiency and retrofit. Also, the Marrakech Partnership for Global Climate Action (part of UNFCC) supports implementation of the Convention climate change ambitions by enabling collaboration between governments and the cities, regions, businesses and investors that must act on climate change. City mayors, governors and other authorities have been busy planning their way towards decarbonisation. The plans presented on the day are all very ambitious, normally aiming for net zero well before 2050 and in some cases even carbon positive.

Most of these strategies start with ambition: set a target first, and find a way to achieve it later. This may be a press stunt in some cases, but surely focuses the mind and the political kudos of leaders. Once the target is set and committed to, a roadmap is developed to try and achieve it. But how? There seem to be a definite pattern: zero carbon public transport first, renewable energy supply as quickly as possible, campaigns and devices to dampen demand and change lifestyles, measures for the decarbonisation of industrial processes, followed by existing public buildings and new regulations to make new construction more efficient. The medium-sized town of Manizales in Colombia prepared a ‘Low Emission Development Strategy’, including an inventory of emissions, identification of climate risks and an integrated management plan. Lower income countries also focus quite strongly on programmes to ensure small businesses and communities know how to operate within this new framework. Only one city from the developed world, Turku in Finland, mentioned people’s centred programmes, something they called learning “1.5 C lifestyles”. Paris, Barcelona and Buenos Aires presented target driven programmes of reclaiming streets from the cars and very ambitious street planting and shading plans.

WHO urged reconceptualising sustainable transport to realise that is not primarily about moving people in a sustainable way. It is about living well: supporting an equitable distribution and efficient use of land, promoting activity and community spirit, enabling children to be safe and independent, allowing employment to locate locally and more. This is a mindset shift: transport to enable people to stay where they are and live fulfilling lives, connecting local to global and preventing separation of uses, commuting and huge land consumption.

Is all this potentially game-changing? I’m not so sure: clearly it is good that mayors and governors step forward when national governments do not give direction. But what about the smaller cities that do not have mayors or resources? 9 out of 10 people live in them! Also, while these programmes are vast and challenging, they are hardly comprehensive or truly visionary. They do not fully respond to the young people on the street that demand a new model, based on balance, fairness and good living. They do not really address spatial efficiency, nor promote truly integrated communities. They improve but fail to deliver deep systemic change and reinvent our future.

These are hugely missed opportunities. Spatial planners have not been very active so far in this stream of action: perhaps waiting for international bodies like UN Habitat to take the lead, or for nations to finally integrate mitigation and adaptation into local, national and regional planning as urged by point 9 of the Glasgow Climate Pact. UN Habitat has indeed announced it will form a Cities Task Force and revisit the New Urban Agenda through the World Urban Forum. But we are running late, and the missed opportunities of today will be difficult to undo for decades: planners like me must definitely up the game and match up the disruptive commitment to change that is emerging in other sectors.

COP26 Official videos

Loss and Damage – the experience from the frontline

- Hearing from the Frontline UNFCCC – COP26 (streamworld.de)

- UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency: A human crisis: climate change and forced displacement UNFCCC – COP26 (streamworld.de)

Young People’s Events

- The official position of YOUNGO: Unifying for Change: The Global youth voice at COP 26 UNFCCC – COP26 (streamworld.de)

Gender equality

- Advancing Gender Equality in Climate Action UNFCCC – COP26 (streamworld.de)

Alternative Economics

- Short – International Society for Ecological Economics – By any Legal Means Necessary UNFCCC – COP26 (streamworld.de) and A New Economics to Face Down Constant Growth UNFCCC – COP26 (streamworld.de)

Forests agriculture and indigenous people

- Facing the Facts Unpacking the Forest, Agriculture & Commodity Trade Dialogue to Tackle Deforestation UNFCCC – COP26 (streamworld.de)

Cities and Built Environment

- RTPI event at COP26, with Maimunah Sharif (UN Habitat) and Martina Juvara (ISOCARP) RTPI – Live Stream (livevideostream.co.uk)

- Building Back Better: Accelerating deep collaboration for Built Environment climate action UNFCCC – COP26 (streamworld.de)

- Unlocking Net Zero in Cities Through Sustainable Digital Transformation and Innovative Solutions UNFCCC – COP26 (streamworld.de)

- Marrakesh Partnership: Cities, Regions & Built Environment Day Action Event: Decarbonizing and adapting our Built Environment and Cities UNFCCC – COP26 (streamworld.de)

Transport and Innovation

- Accelerating the ZEV Transition: A One Way Street UNFCCC – COP26 (streamworld.de)

- Green shipping corridor Launch of the Clydebank Declaration UNFCCC – COP26 (streamworld.de)

- Short: University of Cambridge: Accelerating Aviation to Climate Neutrality UNFCCC – COP26 (streamworld.de)

- Future of international road Freight UNFCCC – COP26 (streamworld.de)