by Max van den Berg, ISOCARP President 1999-2003

Foreword by Jef Van den Broeck

Chair 50th Anniversary Celebration Committee

We all know Max van den Berg as a charismatic and enthusiast professional, member and president of ISOCARP caring for the quality of space and place but also for the living conditions of people all over the world. In his maiden speech as president in 1999 he was pleading for the development of new planning methods and approaches taking into account the new demands concerning mobility and sustainable urbanity within a changing socio-political context. A context characterized by the development of a network society and a growing claim of people and citizen-movements for a fundamental involvement in planning and decision making. He was attracting the attention of planners to the importance of communication and collaboration as a challenge for the future of the discipline.

In this paper Max sketches the evolution of the spatial planning issues during 50 years in relation to the changing context and the role and activities of ISOCARP. It is certainly a personal interpretation of reality founded in his rich experience and involvement during this period. I am convinced that Max believes in the necessity of planning and the fact that planning matters and can change reality in a certain sustainable direction on the condition that planners ‘renew’ themselves permanently by knowledge creation, visioning and active involvement in the planning fields and in society. He also believes in the role of ISOCARP as a kind of catalyst between members, young and old, academics and practitioners and between planners and society.

Unfortunately the health of Max is not optimal today and he will not be able to attend the coming congress in his homeland. But nevertheless this condition he wrote this paper as an incentive for all planners to understand and revisit the history in order to develop new visions for the future including the future of ISOCARP which is very near his hart. Of course we wish Max a full recovery and we can stimulate his recovery by reacting on his paper on the website. With this paper Max invites all members to start such a discussion about the future of planning. Indeed the changing socio-political context, the kind of new spatial issues and their scale, global and local, and new tools and instruments in the digital world will influence the planning profession. Another publication which will be produced within the scope of the 50th anniversary ‘Five decades of knowledge creation and sharing’ by Judith Ryser, is asking also for such a discussion about new directions, visions and concepts. If we want that ‘planning matters’, it is a fundamental joint task.

Thank you Max van den Berg.

50 years of ISOCARP, past, present and future

50 years of ISOCARP, past, present and future

Developments in planning 1965-2015

by Max van den Berg, ISOCARP President 1999-2003

ISOCARP was founded to improve planning practice through the creation of a global and active network of planners. ISOCARP encourages the exchange of major planning issues, ideas, thoughts, planning products and visions, planning tools, methods and instruments among practicing spatial planners in an open colleagial way.

The author wants to highlight the visions and activities of the organization and to situate them within a historical social-spatial context.

The text is not meant as a scientific article but as a personal interpretation of the author looking back in time.

1960s: belief in a new and modern society

Context

A striking international event was the “man on the moon”. It showed the very optimistic confidence in the future. Thanks to an innovative industry steered by ‘Fordism’, the economy boomed and brought full employment and better income. In socialist countries the state dominated, in democratic countries liberal market forces had their share. Society prospered and started to consume: the welfare state was born. The family, with great expectations for their future, was the cornerstone in society. Society was manageable, governments setting clear goals supported by advising physical planners executing government policy. However the student revolts in some countries demonstrated an unease of the population with some consequences of the welfare state for instance the growing gap between the rich and the poor and also with the lack of participation in decision making. The status of physical planning was high due to the huge need for reconstruction after World War II, the need for housing the fast growing population and the economic development.

Physical planning topics

The extension of cities and deconcentration in regions stood high on the agenda but substantial suburbanization of housing went on due to missing spatial frames leading in many countries to ad hoc spatial policies resulting in ecological problems. However planners, using their design capacity, proposed urban and regional comprehensive concepts: “garden cities and “new towns” and pleaded for -“healthy” towns and cities with much open spaces. All over the globe inspiration was found in “modernism” advocated by CIAM (Congrès International des Architects Modernes): Brazilia, Chandigarh, Ankara, Berlin, Paris, London, Amsterdam. The planning field was dominated by town designers and city planners. Planning methods were top-down with the use of a comprehensive planning approach: “survey- analysis-before plan” propagated by Patrick Geddes already in 1915. On all scales “blue prints” were practiced. Implementation in some countries was done by (governmental) institutions and public investors using a strict public management. In other countries development was steered by individual initiative and private land owners. The countryside was dominated by agricultural interests. Nature protection and the development of recreational areas were just beginning to get shape.

ISOCARP activities

ISOCARP activities and congresses are a witness of what happened in society. The 1966 congress dealt with the need for and the policy aiming at regional urban and economic development. The 1969 congress focused on mobility issues. Indeed the growing use of cars introduced new infrastructural models influencing the spatial structure fundamentally. In that congress planners pleaded for the ‘Integration of public transport in town planning policies’.

In 1975 Sam van Embden, one of the founders of ISOCARP and the first President, presented his “State of the Profession” questioning the bureaucratic trend to consider planning as a way to create legal certainty by using rules, prescriptions and land use plans limiting freedom.

……“Is it not so that planning itself, omnipresent, inescapable, is resented as an always farther increasing restriction and narrowing of freedom, as a regimentation of life, as the end of all adventure?

And would not the impact of this experience on the mind of men be much stronger than the somewhat poor qualities of their daily environments?

Here we are on the horns of a dilemma, for there is no doubt whatever that we simply cannot stop, or even slow down, planning and organizing without immediately endangering the existence of the three, soon six billion inhabitants of this planet. But the more these planning-systems will extend and tend to organize their lives, the more each separate individual will feel exasperated and the stronger it will scane the restrictions laid upon it in the name of the Community.

The only answer I would know to this dilemma for the moment refers to a renewal of our mental disposition.

In the first place it concerns those who have to accept planning, but also (and from our point of view this is the most important side) of those who are actively involved in the planning-work. For all of them the main objective should be to find out how to plan freedom.

In my opinion this means: to learn how to plan as if we were not planning. This is more a question of mental attitude than of method, more of wisdom than of knowledge. To this, just as to every other really fundamental problem, there is no real and lasting answer. Each new generation will meet it under another appearance, each generation will have to find its own solution.

We should search for ours. And it is for that purpose that I put the question here”.

1970s: a crisis tempered optimism

Context

The world suffered under an energy crisis and society faced recession which tempered optimism. The international labour migration grew and the just developed care- and service sector stumbled. But on the other hand emancipation and new lifestyles developed especially among the youth. All kind of movements emerged and set the stage: the peace movement, woman emancipation, movements for environment and nature asking for direct interventions, action (the future is NOW), for social-political renewal and participation. Governments got under attack and democratization (“power to the people) was forced which resulted in a polarized political situation. Planning with and even by the people was an often heard adagio.

Physical planning topics

Deterioration of cities became apparent. Urban renewal with “rehabilitation” and “reconstruction” got high priority. Beside top-down planning bottom-up planning aroused with the participation of people in the plan and decision making. Pressure and action groups attacked local governments. Process planning in small steps with emphasis on participation and ‘democratic’ decision-making was introduced. Influence of physical planning experts diminished in that decennium and social sciences became an important field of knowledge, in visioning and in the making of plans. Jane Jacobs inspired society and planners with her book ‘Death and live of great American cities’. Urban management was developed to improve the quality of daily life in cities and process planning became more important than design or plan making.

In the countryside tension grew between agriculture and nature preservation. Infrastructural and transport concepts dominated spatial planning and in general regional planning became grown-up using the comprehensive planning model and zoning and land use plans as instruments.

ISOCARP activities

It was an active ‘ISOCARP decennium’ focusing on diverse topics but all of them related to the societal context expressed in the congress themes: ‘Physical and economic planning’ (1971), ‘Integration and segregation in urban land uses and activities’ (1973), ‘Urban planning and political decision’ (1974), ‘Demands on land’ (1976), ‘Urban change and urban structure’ (1977), ‘Evolution of urban and regional planning’ (1978) and finally ‘Planning and energy’ (1979). In this decennium planners became aware of the relationship between planning, society and politics sometimes forgetting the role and the capacity of their own discipline.

At the congress in 1978 ISOCARP President Gerd Albers stressed this relationship in regards to politics and public participation but strongly advocates the importance of design in planning:

…..’ Planning has come to be recognized more widely as a political task, as a procedure to choose between possible alternatives in the allocation of spatial and financial resources. The awareness has grown that, behind such alternatives, there are not only technical and aesthetic variations, not only different ways to attain a given goal, but more often different goals or combination of goals – or even different concepts of society.

….A similar trend is apparent in the procedure of planning: the political implications lead to an increased sensitivity of planners and politicians to public opinion, this is reflected in the emphasis on public participation and on other means to improve and to make more transparent the processes of decision making. Consequently, we encounter new interpretations of the planner’s role in society. He seems to be bound by a double loyalty, as it were: to his authority and to the people involved – two different manifestations of his abstract client: society.

…. This has also to do with the realization of possible “limits of growth”, with the depletion of resources and the increasing difficulties to dispose of the waste of our industrial civilization….

….. All this has nourished considerable scepticism directed toward the products of modern planning and modern architecture, and has strengthened the tendency to conserve the buildings of earlier periods as documents of continuity and of local individuality. The European Architectural Heritage Year was an indication of this turn of the tide: it would not have been as successful as it was, were it not for an underlying disposition of many people to mistrust change and to stick to what we have. This holds some dangers in store for rational planning: conservation may easily be overstressed, overloaded with too high expectations.

…. We are going to face more criticism, more challenging of goals and procedures of planning than before. We must count on continuous political interest in – and interference with – planning. The planner will have to respond to it – becoming more alert in the political field, adapting himself to the discussion with the public. The planning office as a seclusion to think about future developments recedes into the past: more objections, more hearings, more law suits, more press conferences are in the offing; and we cannot afford to stay out of them, because otherwise our cause will suffer. This is not meant to be an elegy; the integration of planning into politics is a price to be paid for an increased influence on reality – in contrast to the splendid isolation of earlier times with a much more secluded role, but with the disadvantage of not being listened to. Still I feel I should sound a note of warning against “over-politization”. What is needed is political consciousness and a sense of political responsibility; this does not necessarily mean political partisanship.

……The International Congresses of Modern Architecture stated nearly 50 years ago that they wanted to put architecture and town planning back on their real plane: the sociological and economic. Since then, social and economic goals have been considered paramount -and I should add: rightly so. However, this has led sometimes to a neglect of the qualities of the space itself, regardless of its service function to society and economy. This is clearly reflected in the increasing criticism directed against planners for their failure to take account of ecological and aesthetic problems. Different though these fields may be, they have in common that they derive directly from spatial conditions, from the autonomy of the environment. That does not mean advocating the neglect of social and economic considerations: they still are of primary importance. But it does mean to acknowledge the importance – and the acceptance – of planning issues relating primarily to ecological and aesthetic considerations. Here also, we have the problem of a balance between competing demands – and the planner is the one who is called upon to find it’.

1980s: stronger market forces appear

new spatial challenges and opportunities

Context

Disarmament gave us hope for a more peaceful world. Economic growth came back thanks to large scale advantage of merging firms and internationalization. In society individualization won and solidarity lost its meaning within an appearing neo-liberal context which is not the most optimal planning environment. The new rich and new poor took shape. Resources for government became limited, commercialization and privatization got room. The private sector became involved in public goals and worked together with governments. On the one hand ‘collaborative/communicative planning’ became a new model aiming at the cooperation between all involved actors including citizens. On the other hand using a more strategic approach, planners tried to fill the gap between planning and implementation.

Spatial planning topics

After suburbanization of housing also urban functions left cities and even urban regions. Urban redevelopment was an answer to this trend. Revitalization of city centers became important with the focus on mixing urban functions including leisure, culture and high quality of public domain as meeting places of society. Urban concepts were “compact cities”, “waterfront” and ‘brown field’ developments. Within this context ‘the urban project’ appeared as a strategic and concrete tool to innovate the city – first in the Southern European countries often using important events as a motor such as the Olympic Games in Barcelona and the IBA (International Building Exhibition) in Germany.

Market forces became stronger. Strategic planning was a new method to balance goals and means and to involve the many actors. Collaborative planning was born. Action, interaction and transaction between politicians, citizens, experts and entrepreneurs developed slowly. A better implementation was gained in combining public and private investments.

In the countryside nature, landscape, recreation, cultural tourism became as important as agriculture. An integrated approach in spatial planning for regions was the result.

ISOCARP activities

Looking at the congress themes in this decade the relation between social-political and spatial development was obvious. They dealt with the revival of the city, the growing periphery and the metamorphosis of the open area, with a new strategic thinking and strategic tools, with the need for collaboration and cooperation, and with appearing social issues: ‘Renaissance of the city, how?’ (1981), ‘Habitat for all’ (1982), ‘Planning and actions for shelter for the homeless’ (1983), ‘Implementation of planning: the partners (1983) and agents of action (1984), and non-governmental actions (1985)’, ‘Urban and metropolitan peripheries’ (1985) and ‘Communication technology and mobility and their impact on urban structure and form’ (1989).

In their ‘state of the art’ different presidents highlighted aspects of the changing world and planning context.

In 1981 the ISOCARP President Lanfranco Virgili stressed the mediating role of planners in a complex world:

…. ‘The planner has to devise, to propose solutions – respecting the main lines defined earlier and preserving the future. His profession evolves more and more towards the task of mediator, of negotiator. He has to listen, without prejudice, and to understand the different actors in each sector, to help them in the dialogue between them, to perceive the collective interest. And there, the planners are on the edge of a razor, facing influences of contradictory interest groups. Urban projects are firstly of a political nature, which progressively materialises through operational actions. The planner has to take care of translating and rewriting these actions – through dialogue which he stimulates. He has to propose an operational methodology, elaborate the programme and the documents and to monitor and control their operational implementation while being well aware of not signing away future options. But we should not forget that the planner is subjected to moral, social, political pressures of conflicting interests in the transcription of a political urban project. In all these steps, there is risk of failure of initiative! Planners participate in actions which can have effects on economic and social justice. Their proposals and transcriptions can lead to profits for some and to negative consequences for others and at the same time create privileges and disadvantages. Thus this major responsibility implies a great rigour for planners, an ethic, a deontology which, although they apply to the planning profession as a whole are essentially personal’.

Derek Lyddon advocates in 1984 a charter and a framework for making spatial arrangements in a world of rising market forces:

……’ there is a crisis of identity as to who we are: a crisis of purpose as to what we do: and that therefore the profession is in a critical state.…I wish to suggest that our profession has now grown to a state when we can resolve the crisis: We are ready to move from a critical state to a stable state. ……How can we do it? I suggest two initiatives:

- An ISOCARP Charter which states what physical planning is and what planners can contribute to the improvement of human settlements;

- An ISOCARP Framework into which we can weave our work so that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts; greater than the results of each individual congress; and so that stability becomes fertility and continuity.

……Basically I suggest we are making arrangements for the future use of space by people: and we attempt to secure that those arrangements are carried out…. We note however that planning is also the management of uncertainty.

……I erect 5 pillars or essential components of the planning system as follows:

- Definition of type of change in the use of land or building, which is to be the subject of the arrangements.

- The allocation of a right or power to make the arrangements (i.e. to plan).

- The need for permission to make the defined changes (separate from permission to build).

- Right of appeal against refusal of permission.

- The means of making arrangements at different scales, resolving conflicts between scales.

……function asks for analysis, but form based on function seeks for synthesis. Analysis of function relies on words and numbers, but form is based on revealing spatial relationships, through the visual image at a variety of scales simultaneously. We offer a view of the urban or rural tissue, a vision of the shape of place which responds to the territorial imperative for physical identity.

…..In summary I have tried to suggest that after 20 congresses, 5 seminars, and 3 presidential reviews of the State of the Profession our Society and our profession is now in a state when we can and should:

- Resolve the crisis of identity and respond to the crisis in human settlements by stating who we are and by announcing what services we can offer.

- Evolve a framework for co-ordinating our discussions and seeking wisdom with humility’.

Manuel da Costa Lobo describes in 1987 new trends and uncomfortable issues in a globalizing world:

…….. ‘Last Year’s Main Trends

Besides the general evolution in town planning and in the role of professionals which I referred to before it seems possible to think about the developments in planning over these last 3 years. Let me suggest 7 points to stimulate your thoughts:

- The population of industrialized countries is declining in number and in number of persons per family, most of them getting more sophisticated jobs which often leads to strong labour force migrations, even between continents. Demographic increase in developing countries is still going on but shows, here and there, some signs of slowing down.

- Ecological disasters are becoming more frequent and known and society is becoming more conscious of the decline of natural resources and of the danger of hazardously taken decisions with negative ecological side-effects.

- Cultural heritage conservation is becoming a subject of high priority for governmental policy. The awareness of cultural and architectural heritage values is increasing very rapidly. A theoretical approach is being developed and conservation is being included in the aims of political programs. Rehabilitation has been the subject of research and experiments. Creativity of professional planners and architects demonstrates that it is feasible and positive to bring the past back to life. This is the new direction of urban development, much richer, much more human and more promising.

- The well-known interdisciplinary and systematic concept of planning is developing new formats, being more integrated, open to new sciences and professions, and experimenting interschool training courses.

- A new boom of planning is taking place in several places. Professionals are organizing themselves within national and international associations of planners, and experiments have been undertaken with new formats for plans and planning. As far as non-planning has been tried: facts showed its failure – a kind of trap for public administration and people in general: less coordination, malfunctions, economic losses and utopic increase of personal freedom, only possible beyond planning limits by reducing the freedom of others.

- Land used as a capital good is increasing very rapidly and its acquisition for economic investment is becoming a general concern all over the world. Prices are going up and land turns out to be an alternative to gold. It became an important component of the planning strategy. Agricultural land is therefore decreasing, landownership is being questioned and a kind of anxiety touches millions of families…….

……Uncomfortable Issues

Coming to the point we cannot be happy about what is going on. We know that public administration, investors and planners are too often making wrong plans, not fitting with reality, bringing side effects that are worsening the urban environment and the life of people. Planning is making people homeless, planning is forgetting homeless people, planning is suggesting long-term improvements and does not care about today’s dramatic situations, planning is presenting misleading policies and actions to people, planning is shown through plans in an inadequate format. But we know that every day is good enough to change our attitude towards ourselves, towards our neighbours and towards the world population in general. Human culture has become more and more universal from the 15th century onwards and it is time to reach maturity, to feel that solidarity is not only a moral duty but also a natural development of human nature in the struggle for survival. We must be aware that most actions we launch are very often too late, though the essence of our profession is to anticipate problems. We still have a long way to go. We have always been stressing that planning should integrate all facets of life. A relatively new planning approach is the high priority given to our environment and eco-systems. Our economic systems should take into account the environment. That is the basis for a correct planning approach. We must take action to get the needed changes. Planning must be in the centre, to help big decision making, but must also develop to the periphery, where people and urban buildings are. The two-way feed-back is essential for the strategic component of our job. We cannot be honest with ourselves without feed-back and putting research in practice into impact studies. We have to go on fighting: fighting for peace, fighting for participation and fighting for more professionalism’.

1990s: globalization, migration and new technologies

Context

Borders in Eastern Europe vanished and Europe became an influencing actor also in regional and urban development. People became more mobile and PCs and internet facilitated a more “Global World”. Information and communication technology brought limited economic growth all over the world. Food production increased, but did not bring welfare everywhere. Mass migration, social segregation, fragmentation, refugees and homeless people became apparent and right wing parties appeared in the political world. Market forces, big (banking) firms with shareholders gained influence and power within a growing neo-liberal context. Politics re-oriented itself and public planning and planning services got under pressure and started to shrink.

Spatial planning topics

Because of the growing awareness of spatial key-issues spatial planning, infrastructure and environmental policy became integrated. Ecological quality, nature protection and water management appeared as important policy fields. Internationalization and regionalization went hand in hand trying to combine global and local issues and policies. Multifunctional land use was encouraged. Interest groups but also citizen movements became important setting the stage. Negotiation and agreements between actors, the creation of alliances is part of methods in planning processes. Planning products accepting sprawl and deconcentration as a reality, are for instance concepts like “patchwork metropolis”, “edge city” and “metropolitan regions” and “Zwischen Stadt”. But also the development of often well located brown fields and urban voids were seen as an opportunity for the strengthening of cities and urban areas. Problematic urban regions started with an ‘innovative integrated area focused development approach often stimulated by the ‘EU Regional development policies’. Examples are Bilbao in Spain, Emscher Park in Germany; The Ghent-Terneuzen port area in Flanders/Netherlands. Essential in these processes were the development of a long term vision related with a concrete action program and an action plan as well as a collaborative approach based upon agreements between actors. The urban programs of the EU stimulated cities to innovate focusing on deteriorated and poor neighborhoods. Cooperative actions resulted in more private investments even in the public domain but under the direction of a public agency. Sometimes contracts replaced plans and sometimes plans are the contract. In the countryside multi-functional land use developed. Ecology and environmental issues were important like clean water, diversity, priority to “natural” nature. The urban field and countryside came together.

ISOCARP activities

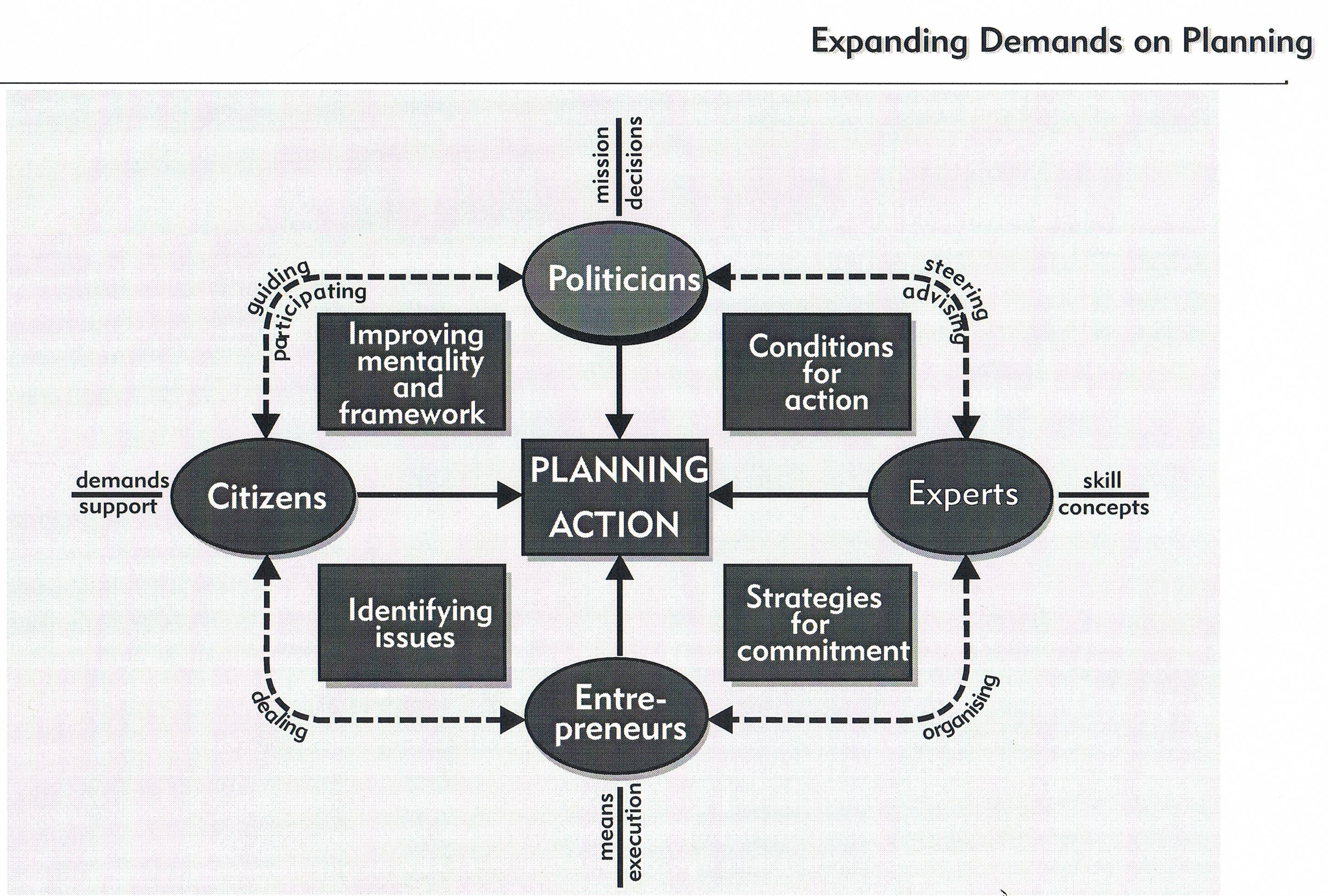

The congress themes reflected these social-spatial key-issues: ‘Environment and the city’ (1990), ‘Planning for leisure’ (1991), ‘Cultural identity and unity’ (1992), ‘City regions and well-being’ (1993), ‘’Expanding demands on planning’ (1994), ‘Adaptation and mediation in urban planning’ (1995), ‘Migration and the global economy’ (1996), ‘Land and water’ (1998), ‘The future of industrial areas’ (1999).

As General Rapporteur of the 30th congress in Prague (1994) the author of this article Max van den Berg said:

“There is a need in all countries from time to time to redefine planning in response to changing demands. We have to restate in the language of each country that the essence of human activity called “planning” is: making arrangements for the future….”

Actors in the planning system are:

- Politicians: they have a mission and take decisions

- Experts: they have knowledge and skill, make visions and plans

- Entrepreneurs: they have means for investments and organise implementation

- Citizens and institutions: they have demands and ideas and give support.

In the fifth edition of the International Manual of Planning Practice (2008) Judith Ryser and Teresa Franchini wrote:

“Based on the simplistic premise that ‘planning is making arrangements for the future’ it became clear from the early days of congresses and papers of ISOCARP that for each country the question arose: ‘what type of arrangement and for the future of what?”.

But anyhow, what Derek Lyddon, past President, said is still valid: “Planning is a basic human activity”.

Karl Otto Schmid reflected in 1990 on fresh IMPP, on threats in a competitive economy and remarked about expectations of politicians in relation to planning experts:

…….’Since our Society published the International Manual of Planning Practice, with the comparative presentation of planning systems in a dozen countries, some of us experienced a sigh of relief. The very substantial efforts behind this publication remained mostly hidden. In researching the fundamentals of planning legislation and some characteristics of plan implementation in every country which is represented in the book, the comparison reveals a lot of common ground. It gives you the impression that we must be doing the right thing….There is very little evidence that urban planning is more efficient in one country than in another because the planning processes are more or less centralized, more or less legally determined, more or less submitted to citizens’ participation, different in methodology, private sector involvement, etc..

……There are equally enormous differences in the perception of what is most dominant among the goals of planning, in the sophistication levels of planning, in the resources allocated to planning, in the known levels of effectiveness, in the transparency of the planning processes, and many more.

……’All planning efforts, in every country, reduce a complex reality to manageable proportions of this reality’.

……’Several adverse trends can be identified among the political reactions to the inadequacies of planning:

…..Abbreviation of the Planning Process:……There is a long legal procedure in most countries for the implementation of planning policy, before general options for political action, general planning concepts, general goals and the like can be translated into specific operational measures.……For several reasons political impatience will result in an attempt to abbreviate the process..….Whether such short cuts result in circumventing legally prescribed procedure, or whether political leaders take the matter out of the hands of law-abiding planners and submit it to emergency measures, our profession is seriously affected.

……Consultation of Specialists from outside the Planning Profession:…..In real crisis situations, e.g. when we confront serious environmental problems, or when millions of new jobs and homes should be generated almost overnight, political leadership tends to consult with specialists who promise quick delivery and who address only the urgent issue at stake.

…….To conclude my analyses, if urban planning is in an advanced stage of sophistication, and if the chances for centrifugal forces and for confusion are equal to those for integrated approaches towards adequate action, one thing is clear – our profession is very much alive and as exciting as ever’.

Javier de Mesones had a philosophical statement in 1993 about attitude and change:

…..’The world population grows daily at the frightening rhythm of about 200.000 people, which means theoretically that every 24 hours one new team of numerous planners could devote their whole life to design, build and manage a new big city. It seems that there is no shortage of work. Under these circumstances, the “planner’s role” is often considered as a theme of top interest, probably because it is supposed that the planner, in permanent confrontation with change, has to constantly modify his position and to adopt always a new and different attitude with regard to a society in a non-stop evolution.

……The evolution and development of mankind in its demographic, cultural, social and economic aspects is the engine of change. The physical and legal reflection of change over the binomial city/region is the object of planning. To answer conveniently to change, planning often has to alter the delicate balance between urban and rural land, sometimes by urbanising rural areas or, at other times, by intensifying the use of certain urban areas that also were rural in the past. Every intensification of use, both the change from rural to urban and the increase in quality or quantity of its potential use, implies an added value, in accordance with the inexorable law of supply and demand.

It is evident that planning has the power to generate added values as an inseparable consequence of its proper object, and as a result of its specific activity. The logical and unavoidable generation of added values has to be done where change requires it, that is to say, where it will be more positive for development.

The planner has to fully justify his decisions and to adopt his determinations in the most scientific way, always along the principle of sustainability of the proposed development. But do not be mistaken! Let us be sincere, at least with ourselves….. Decisions are not taken only by planners.

They have, in each case, to design the plan and to shape it in accordance with decisions adopted by others. Who these other partners or agents are has been the topic of some of our past congresses. When the proposals are promoted by economic agents, the political – administrative agents and the planners are responsible for their analysis and approval – or rejection.

When the decisions come directly from political – administrative agents, without prior technical justification or without full cooperation with planners, the decisions might seem at least suspicious.

In many countries Land Acts establish fairly that a part of the added values has to revert to the society whose evolution justifies and produces the change. This premise is only applicable at the end of the process, once the real added values have been generated. It often happens that the one who obtained the profits has vanished by then’.

Serge Domicelj stated in 1996

……’Undoubtedly, in the mid-1990s, the planning profession has continued to diversify in both perception and application. At times operations have become further specialised while at others the need to be comprehensive has grown even more paramount. An intractable globality and a tenacious localism have both become entrenched, often in opposition, and requiring planning intervention.

In industrial countries, the environment and technology, reactive or proactive, now form the professional mainstream focus, but one which lags behind scientific advances. In developing regions, sectoral emphases continue to characterise the nature of planning practice: economic inputs in Asia, geographical ones in Africa and the sociological in Latin America.

In industrial countries, after a declining concern for planning during the 1980s, a resurgence, with global implications, is manifest in the mid-1990s.

Some tendencies are:

– a search for more participatory and collaborative urban governance;

– an emphasis on decentralisation, devolution and support for local government and;

– continued attempts to eradicate poverty.

…..Last year Erik Wirén warned us of current challenges to planning from pervasive global influences, unregulated market competition and scientifically based systems which, when taken together, could negate the need for the planning profession. And yet, in the face of unmanageable crises, the need for planning physical environments has heightened and is recognised even by endemic marketers.

……Simultaneously, quite different opportunities for engaging planners may result in a close cooperation with communities, with their regular involvement in the provision or rehabilitation of local services and places. However valuable, such interventions often go unrecognised, leaving the impression of insignificance in the face of powerful pervasive forces, which originate beyond the local environment and away from its control. Although leading to community improvement, such planning efforts have not created the sustained development of human resources, and may result in the loss of professional status. One conclusion is that the concentration of strategic resources on the one hand, and the sustenance of cultural diversity on the other, have contributed to the proliferation of planning roles, in response to different clients and requirements…..the profession has lost focus rather than credibility.

A matter which is fundamental in our uncertain times is, the perception of planners’ roles, whether inside or outside the profession. I feel the critical need for two roles to be exercised: the reformers (such as advocate planners) and the synthesizers (human strategists). One consideration is that, in pursuing traditional social aims, planners should improve the effectiveness of their delivery to the community, and so clarify their professional focus. This will only be achieved by tackling diverse problems in a range of circumstances by different means. In practice, the scale of demands will only be met if planners secure extended partnerships and further define their own roles’.

In 1999 Halûk Alatan advocated spatial planning competition and cross border projects:

‘As physical planners, as ISOCARP, what can we do and what should we do? I would like to draw your attention to two issues: First, international physical planning competitions. Competitions are a means to bring planners together to work for a joint aim. International competitions offer a milieu where, besides new ideas and opinions being presented and compared, planners, executors, representatives of culture and politicians are brought closer together. The international Gallipoli Competition last year, converting First World War battlefields into a Peace Park, is a good example of this. 120 participating planner groups worked and competed to create an idea of how to turn the cold and cruel face of war into a Peace Park for international peace and humanity.

……ISOCARP should…..support the idea of organising all kinds of competitions on different scales. These competitions are projects requiring teamwork. In consequence, it does not only bring about closeness between countries and understanding for each other’s problems but also enhances the solidarity and co-operation between different professions. One of the most beautiful aspects of our profession is that it gives us the pleasure to work together, to search for and find solution together….. As our founder, Honorary President Sam Van Embden said 20 years ago: “We have to enrich our work by finding the balance between imagination and reason.”

The second issue I would like to draw your attention to, is the support to and increasing the number of international, even intercontinental physical projects. As an example, I would like to present to you the Silk Road Project, which has entered the agenda lately. Once in historical times, the Silk Road was a corridor from Japan and China through Middle Asia and the Caspian Sea to Black Sea and from there to the West, to Europe. At that time, the main reason for this link between East and West was silk, but the important rehabilitation project is based on the attractiveness of oil. The richness of oil in the region of the Caspian Sea, the largest inland sea of the world, is of course the basis of West’s interest in this Eurasian project. A modem infrastructure must be built in order to transport the natural resources to the markets in the Western world…..It must be our most important duty as planners to safeguard the protection of environment, nature and historical values on all scales, and the peace, well-being and stability between communities and people.

We should make this project, crossing boundaries and bringing nations closer to each other, a “Project of Hope” for the mankind. Ibis road will not only connect countries to each other but also history to future’.

Within this decade ISOCARP strengthened relations with international institutes. Highlight was the presentation of an ISOCARP report at 1996 UN Istanbul FORUM by Serge Domicelj about ‘Partnerships and roles’:

……’The Forum’s report states that planners need to redirect their sense of professionalism, recasting the current understanding of skills, performance and, ultimately, service to the community. This implies new knowledge, information deployment and ability to negotiate in situations of conflict. First, a new understanding of civil society, governance and the nature of public resources is thought to be essential in creating alternative paths for human development.

Second, there is the need for new information, as the basis for a ‘social production of knowledge’ (Malusardi). A fortunate phrase which considers at least two systems: one translating the use of natural resources into everyday terms and the other ensuring their informal, creative use by disadvantaged communities, in their unorthodox quest for improvement. Third and fundamental is the development of mediation skills to resolve conflict and to develop amongst stakeholders a sense of shared, or at least mutually respected, goals.

In implementing the above approach, it was thought in Istanbul that professionals should develop a diverse range of roles to extend service within the informal sectors. Through modified forms of expert intervention, they could function reactively, proactively or interactively, according to the specific needs of clients and communities (Srinivas). Professionalism depends on flexibility in the choice of clients and partners, to respond effectively to competing briefs. Finally, and significantly for professional bodies such as ISOCARP, the ability of communities and professionals to establish truly global partnerships gave hope for a more precise understanding of complex development matters’.

2000s: revival of the western city, fast urbanism in the East and environmental challenges

Context

Attack on Twin Towers in New York 7/11 2001. Terrorism and revolutions with ethnic dimensions on several continents. New “I” tools like I-phone, I-pad and I-tablet caused access to abundant information and hyper individualism. BRIC countries had a grow-boost. Global market forces and the private sector got an overwhelming influence. Shareholders’ profits influenced also in non-profit sectors. Governments slowed down and had limited influence possibly except on the local level. Bigger cities and urban regions tried to innovate and to become a driving force in society acting in a competitive international setting. The Mayors’ Summit during the congress in Geneva was a sign of this local revival. Intercontinental migration of refugees and homeless people. Awareness of climate changes and sustainability in general grew slowly. The global bank crisis in 2008 and the energy crisis shocked the world. Crisis and recession overcame the Western world influencing planning discourses and approaches.

Spatial planning topics

Regional as well as urban planning became adult in the Western world. People become aware of the regional dimension of issues: mobility and infrastructure, the housing market asking for different living environments, a new kind of economic development asking for specific locations,… Also cross border (regional) project planning for infrastructure (e.g. high speed trains), for rivers and for delta’s emerged. Water management and “sea” planning were new fields.

Cities believed in their values and role and started with concrete urban policies using different tools, strategic plans, urban projects, the organization of urban events, better public transport and bike infrastructure,… With their world congresses UN-Habitat was drawing attention to the needs in poorly developing countries. Mass housing projects for the poor in urban areas got shape but could not solve the huge demand, certainly not in conflict areas. Concepts and projects for “sea-”, “air-”, “brain-” and “green” ports were developed. Continental nature preservation schemes got legal status.

A new ‘New world’ appeared in the east and introduced new spatial models pushed by the huge demand for housing and economic development: fast urbanism.

ISOCARP activities

The ISOCARP congress themes dealt with all these topics: regional and urban development within a global world, environmental degradation, the need for the involvement of all actors in planning and decision making, the changing economy and its integration within an urban context: ‘Peoples empowerment in Planning- Citizens as actors in managing their habitat’ (2000), ‘Honey; I shrunk the space- Planning in the information age’ (2001), ‘The Pulsar effect: Coping with peaks, troughs and repeats in the demand cycle’ (2002), ‘Planning in a more globalized world’ (2003), ‘Management of urban regions’ (2004), ‘Making spaces for the creative economy’ (2005), ‘Cities between integration and disintegration- opportunities and challenges’ (2006), ‘Urban Trialogues: Co-productive ways to relate visioning and strategic urban projects’ (2007), ‘Urban growth without sprawl: a way to sustainable urbanization’ (2008), ‘Low carbon-cities’ (2009).

Max van den Berg promoted new methods, new tools and stressed the “who” aspects in interactive planning in 2003:

……’We have to understand the contemporary meaning of movement and settlement, of flows, of new regional and worldwide entities. We have to discover new location factors of the network society, modern demands on mobility and new demands on quality of place and settlement……

……More actors are joining the planning scene.

Now market forces, NGO’s, institutions and interest groups ask their share in spatial planning and demand attention for specific circumstances. Governments of states, regions and municipalities are no longer in a powerful position to set the planning stage. Corporate actors demand involvement in planning processes to put their stamp in an early phase of planning. New coalitions arise with ever changing partners. Civic societies, social, cultural, environmental and political movements want to become involved in planning policy. We talk of “stakeholder” and “shareholders”. ……The more actors there are the more communication is needed. Managing communication is a new challenge for the planning profession…….

…..New planning tools are invented: project planning, interactive planning, strategic planning, communicative planning, network planning etc. The desire is better implementation, earlier involvement of actors, the participation of citizens, more ideas and creativeness of all involved……

……Strategic or interactive planning has come into sight. Interactive planning is an opportunity for combining forces and means. Even it extracts hidden financial means, unexpected knowledge and creative ideas. Interactive planning assembles new actors around the planning table. Strategic planning tries to optimize means and aims. It tries to come to agreement on combined input. Combined action is primarily the output. An important phase is the selection of the right actors. Considerations and negotiations as an interactive way of working have to be managed. Strategic planning makes use of concepts, which gives an opportunity to have a long time framework for detailed and fragmented action……

……In terms of process we shifted from “what do we want, how will we do it and who is doing the job?” to “who will do the job, how will they do it and what will be the result?”’.

Within this decennium a new innovative project started: the UPATS, Urban Planning Advisory Teams aiming at the support of cities all over the world. The project was an initiative of Alfonso Vegara, past President (2003-2006). Already for 10 years ISOCARP teams have been collaborating in many cities with local authorities and planners in order to look for sustainable solutions not only to tackle specific problems but to design new exiting visions, concepts and concrete proposals for a better future. Each ISOCARP team consists of ISOCARP experts, older and younger, with different capacities working together during about one week. The teams may not be considered as consultants but serve as ‘eye openers’, as an incubator opening the minds of the locals and instigators for change and innovation. More than 20 UPATs have been organized already:

- 2015, Gaza and West Bank, Capacity Building and Test Planning Exercises for Gaza and the West Bank

- 2013, Tlalnepantla, Mexico, Una propuesta para Tlanepantla Centro

- 2013, Shantou, China, Organic Regeneration of the historic Downtown of Shantou

- 2013, Nanjing, China, Jiangbei New District, Nanjing

- 2012, Perm, Russia, Perm Science City and Knowledge Hub

- 2012, Wuhan, China, Wuhan East Lake Scenic Area Development Strategies and Sustainability Concepts

- 2010, Sitges V, Spain, Cambios en la esstructura ferroviaria: Impactos en la Región del GARRAF

- 2010, Singapore, Livable cities in a rapidly urbanizing world

- 2009, Szczecin, Poland, Szczecin Metropolitan Region

- 2009, Sitges-IV, Spain, Garraf Natural Park

- 2008, Zurich, Switzerland, Limmat Valley

- 2008, Guadalajara, México, Major urban renewal to revitalize the city

- 2008, Lincoln City, USA, Community Vision Plan for the Cutler District, gateway into Lincoln City

- 2008 Cuenca, Spain, Improved mobility, valorising the city centre, reusing land currently occupied by rail tracks

- 2007 Sitges-III, Spain, Determining the strategic role that the Garraf territory has to play in the middle of a growing region

- 2007 Schwechat, Austria, Transform Schwechat into a ‘knowledge hub’

- 2007 Rijswijk, The Netherlands, Rijswijk Zuid

- 2006 Sitges-II, Spain, Urban Mobility

- 2006 Schiphol Region, The Netherlands, New plan for the development of the area between Schiphol Airport and the North Sea

- 2006 Cancun, Mexico, Hurricane Wilma

- 2005 Sitges I, Spain, Urban territorial integration

- 2004 La Rioja, Spain, The Footprints of Dinosaurs

Initially Alfonso Vegara explained the objectives of the project:

‘UPATs are bottom-up self-financing projects that mobilize ISOCARP members for singular urban initiatives with international relevance’.

2010s: which future?

It is too early to evaluate and characterize the present decennium. However we know that globalization is going on as well as the network society with a huge role for communicative media. The market driven society, not only in the western countries, will possibly be confronted with limits: a growing gap between rich and poor, tensions between individual ambitions and collective needs, conflicts and economic differences, huge migration resulting in diverse communities and cities, people’s claim for participation,… Climate change and ecological issues will be global issues and a demand for livability will be local planning issues. What can be the role of planning and planners/urbanists in such a new context? And the role of ISOCARP? The author hopes and expects that ISOCARP will actively keep contributing in creating and sharing knowledge, skills and visions and in the improvement of the living conditions of people in a diverse world. He hopes that this paper can open a discussion.